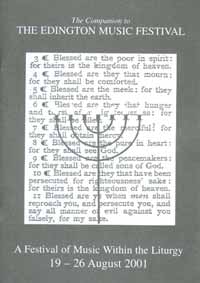

The Edington Festival of Music within the Liturgy 19 – 26 August 2001

The Festival Director’s Introduction

Welcome to the Edington Festival of Music within the Liturgy. I hope that you enjoy its uniquely distinguished blend of beautiful music, fine liturgy and stimulating preaching, and leave this tranquil place both physically and spiritually refreshed.

Over the past few festivals, I have tried to achieve a sense of progression from one year to the next, as well as within each festival. Thus the theme of light in 1998 led naturally to our exploration of Advent themes the following year, in preparation for last year’s millennial Christ-centred theme. I hope that this has proved effective in enhancing the value of each successive festival week. This year, I was keen to sustain this momentum, and to consider Christ’s teaching and ministry: the Beatitudes, succinct yet powerful, seemed the ideal structure and tool for this.

The nine beatitudes at the beginning of the Sermon on the Mount in Matthew’s gospel (as this passage was first described in St Augustine’s commentary 396 CE) have provoked much discussion. Whilst scholars have debated their origins, the most common view is that three of the first four beatitudes, the blessings on the poor, those that mourn and those that hunger, are in fact derived in at least some form from Jesus. In the words of Warren Carter, “they exemplify Jesus’ concerns with the poor and maintain a tension between present experience and future blessing, which many see as reflective of a tension evident throughout Jesus’ ministry.” The blessing on suffering may also have these direct links. It is likely that the remaining beatitudes were composed by Matthew, based on material available to him.

The concept of the beatitude is rooted in Jewish tradition. These statements are examples of a common form known as a macarism, from the Greek for ‘blessed’ or ‘happy’, and in Jewish literature are most common in worship and wisdom traditions. They thus serve both a liturgical and a didactic function, giving us a brief summary of essential doctrine and providing both instruction and assurance. They give clear guidance on ethics and morality.

Although Luke also incorporates a set of beatitudes in his Gospel in the Sermon on the Plain, he only lists four, and it is interesting to compare his with Matthew’s. For instance, it is Matthew who adds ‘poor in spirit’ to the plainer ‘Blessed are the poor’ in Luke, thus drawing our attention to the humility which is necessary in order to be open to the kingdom of heaven. In essence, each set reinforces the message of the Gospel to which it belongs: “Matthew stresses the integrity of inner dispositions and behaviour” (John Bowker).

Our interpretation of the beatitudes can be open and wide-ranging. On the one hand they can be taken as promises of eschatological rewards for the virtuous, along with exhortations to lead a way of life in tune with God’s kingdom, and on the other they proclaim God’s reversal of fortune for those in harsh circumstances. But above all, perhaps, the best way to view them is within the context of Matthew’s gospel, the earlier beatitudes elaborating on the experience of those who have been healed, the later ones commenting on the preaching of God’s kingdom, and delineating further consequences of both present and future blessing.

During the festival, we will focus on one beatitude each day, although there are pairings of beatitudes on Tuesday and the final Sunday. I have undertaken a slight re-ordering of them, in order to present ‘Blessed are they that mourn’ on the day of the Requiem, which this year will be sung to plainsong, with the polyphonic choirs singing an eclectic progression of appropriate motets. On this day, we also consider another form of sorrow implied in this beatitude, that of repentance, mourning also then being a spiritual exercise arising from the humility mentioned in the first beatitude. One cannot become poor in spirit whilst pursuing worldly riches – comfort comes from the Messiah, who was anointed specifically ‘to preach the gospel to the poor’ and ‘to heal the broken-hearted’.

This supreme ambition of spiritual rather than material gain is further explored on Tuesday, the meek receiving a rich inheritance, and the hungry and thirsty being satisfied. Of course, the state of being hungry and thirsty implies something that is ongoing and nagging in its demands to be filled, and draws our attention to the precision with which the beatitudes are worded. Note that it is not hungering and thirsting ‘to be righteous’, but ‘after righteousness’ – an internal need to be satisfied by an external, objective quality. This puts us in mind of what the Last Supper signifies: ‘An exterior material sign of an interior spiritual reality’ (John Metcalfe). Righteousness is at the very centre of the gospel, with all its legal, moral and social connotations. Similarly, the origin of the blessed meekness is spiritual, and concerns one’s state before God. The inheritance of the meek is most vividly portrayed by the promise to Abraham, who (in the words of St Paul) received this promise, “not through law but through the righteousness that comes by faith”. Note that it is an inheritance, thus implying death. Abraham did not five to see his promise, but he did receive this promise of the earth. In the familiar sentence from the Magnificat, ‘He remembering his mercy bath holpen his servant Israel: as he promised to our forefathers, Abraham and his seed for ever.’

‘Mercy’ can be defined as compassion for people in need, and we consider this on Wednesday. In a lovely phrase taken from John Metcalfe’s meditations on the Beatitudes, mercy is, “an ardent religion, the heart of which is love, the medium of which is faith, and the outlook of which is hope.” Mercy is directed towards our fellows, not towards God, and is demonstrative and cannot be faked – either you are merciful or you are not. Much of the music on Wednesday expands on this theme, and I am particularly pleased that John Barnard has composed a setting of ‘Blessed are the merciful’ especially for the BBC broadcast. He and Paul Wigmore have also written a hymn which captures the whole spirit of the week’s themes marvellously for our radio listeners as well as ourselves, in their customarily successful collaboration.

The reshaped framework of the beatitudes over the week presented a valuable opportunity to explore two using the format of the sequence of music and readings. On Thursday evening, the sequence is based on ‘Blessed are the pure in heart’, and ranges from initial penitence and questionings to the kindling of love on the mean altars of our hearts. Purity implies purging or purifying, and is an internal purity, not the external appearances of the Pharisees. It would have had a ceremonial significance for the Jews listening to the Sermon. ‘If with all your hearts ye truly seek me, ye shall ever surely find me’ is a phrase familiar from Mendelssohn’s great oratorio ‘Elijah’, and brings substance to this most spectacular of promises … ‘for they shall see God’. (The aria of course continues ‘0 that I knew where I might find Him, that I might even come before His presence.’) It is this tension of ecstasy and uncertainty that makes this promise so compelling.

Another great oratorio has the following words on its flyleaf: ‘the darkness declares the glory of light’. Sir Michael Tippett’s ‘A Child of Our Time’ is a profound and personal response to a sickening incident during the war, and this concept of a journey from darkness to light underlines the progression of Saturday’s sequence for ‘Blessed are the peacemakers’. This is, of course, a theme I have explored in previous festivals, and is reflected in my choice of Susi Laurie’s Advent piece to be part of the sequence, but the main inspiration behind the structuring of this service is in fact that great peacemaker Dietrich Bonhoeffer. He seems never to have wavered in his Christian antagonism to the Nazi regime, although it meant for him imprisonment, the threat of torture, danger to his own family and, finally, his execution in April 1945 on the direct orders of Heinrich Himmler, in the Flossenburg concentration camp only a few days before it was liberated. In addition to a reading from his own writings, we will be singing Philip Moore’s moving settings of the three Bonhoeffer prayers which act as a backbone for the sequence. There are many other colours to this service: the fact that it is in the evening reminds us of our progression towards the autumnal peace of sleep and death, a journey also reflected in the Moore pieces, and this is musically further enhanced by the contrast of persecution in Purcell’s great anthem with blessed rest in Schütz’s masterly motet.

This leads most naturally to the last two beatitudes, which deal with persecution. We are fortunate in this country to live at a time when there is relative harmony in Europe and beyond, but of course there are parts of the world where persecution is rife in one form or another. Equally, one could consider the existence led by, say, William Byrd (whose sublime setting of the Beatitudes we are singing on this closing Sunday), who was probably only sheltered from a grisly fate by royal favour. These beatitudes remind us that not all attempts at reconciliation will succeed.

However, there is a wonderful promise. The blessed ones are to be set free from the selfishness and greed that surrounds them, and are to follow in the footsteps of no lesser people than the prophets. Thus persecution becomes a badge of genuineness, and in a phrase taken from John Metcalfe’s at times charmingly querky book ‘After all, do you know of any better company?’ Those who trust in God implicitly, even when people, states and nations revile them because of their faith, fulfil their calling to faithfulness even through persecution.

The beatitudes, then, represent an ideal – the first four in relation to God, and the second four in relation to our duty towards our fellow human beings. There are both privileges and responsibilities implicit here, but the future tense has the ring of certainty about it to encourage us. In his engaging study of the Sermon on the Mount, John Stott draws our attention back to the emphasis placed on righteousness, an ‘inner’ righteousness of the heart manifest outwardly in words and deeds. Stott describes the Sermon as a kind of ‘new law’. The law “sends us to Christ to be justified, and Christ sends us back to the law to be sanctified.” Yet behind any complex theological thoughts that I may have attempted to alert us to, there is a disarming and urgent simplicity.

The essence of Jesus’ teaching is the coming of the kingdom of God. Jesus taught in word pictures and stories – the only way to get this otherwise nebulous concept across to a largely peasant audience. The Kingdom of God is the very opposite of all worldly kingdoms – everything is turned on its head. In God’s kingdom the blessed will be the very ones who have counted for nothing in our earthly kingdom.

Last year we said goodbye to a very long-standing friend of Edington, David Trendell. David first came to the Festival as a singer, and then succeeded Geoffrey Webber as a relatively youthful but particularly imaginative Director. A perusal of the Companions from this period reveals an incisive, adventurous and rigorous choice of themes. David subsequently enjoyed a highly productive and successful decade as Director of the Nave Choir, displaying these same qualities in the preparation for and execution of that demanding role. In my farewell speech to him, I mentioned David’s great generosity in sharing his very brilliant ideas about a wide range of repertoire with the rest of the musical team. His knowledge of sacred, and other, music seems encyclopaedic, and yet he wears his learning lightly, with modesty and humour. I find this willingness to give of the best of one’s knowledge and ability one of the most fascinating and rewarding aspects of the Edington Festival. This is a welcome antidote to the outside world, where good ideas or ingenious projects are often jealously guarded. Equally, at Edington there is a pleasing focus to the week – research, experience and expertise all combine and come to fruition under one roof for the good of all: the very spirit of Edington. I was privileged to be educated in this spirit at an early stage of my involvement with the festival, when organist, by another long-term Edingtonian, Robin Blaze. I well remember listening to a beautifully sung Compline lying outside gazing up at the stars, discussing with Robin the glories of the evensong of Gibbons’s music which we had both just taken part in. This epitomises much of what Edington represents to many people on different levels liturgically, socially, intellectually, musically and spiritually.

I have mentioned the many and various facets of the Festival. All these different aspects come together, combine and mix in quite interesting, different and productive ways in the different festival settings: primarily, naturally, in the worship in the priory church, but also in the social engagement at meal times and in the free time during the week. We all have a chance to catch up on each other’s news, views, discoveries, successes and disappointments, and also to catch up with ourselves. The Festival binds church, village, visitors and hosts in one.

The importance of ritual is one aspect that underlines much of this: ritual is essential to the liturgy, but it is also articulated in the secular world in many areas. Since last year’s festival, I have been fortunate to see Harrison Birtwistle’s ‘The Last Supper’ (written for Glyndebourne), music which springs from a fascination with The Last Supper as a moment when human experience is transformed into ritual. Equally, the Rambert Dance Company’s evocative production of Stravinsky’s ‘Symphony of Psalms’ (to choreography by Jiri Kylian) was mesmerising, and fully justified its description as a “compassionate celebration of human spiritual tenacity”. Ritual is all around us.

This year, in addition to the commissioned introit from John Barnard (for Consort), I am thrilled that our new Festival Organist, Matthew Martin, has written a communion motet for the Nave Choir. It is also pleasing to be able to perform in a liturgical context a number of other recent works – by Robert Fokkens and John Sanders, as well as by the aforementioned Laurie and Moore. I am delighted to be continuing the strong tradition of renaissance music at the Festival, notably by using David Trendell’s recently published edition of Lobo’s ‘Missa 0 Rex gloriae’, in addition to a wide ranging continental blend of liturgically apt motets.

My thanks, as ever, are due to all the aforementioned people, and also to Peter Roberts and Clare Dawson our administrators, to choir directors Jeremy Summerly, Andrew Carwood and Robert Quinney, to organists Matthew Martin, James McVinnie and Andrew Macmillan, to Ian Aitkenhead and Nick Flower for their help with the Companion, to Joy and Michael Cooke, Jonathan Arnold and Justin Lowe for their work for the Festival Association, and to David Belcher, Jean Hall, John Barnard, Adrian Hutton, Christine Laslett, Antonia Southern, Pat Didcock, Gilbert Green, John d’Arcy and Jeremy Moore, who all do so much to ensure the Festival’s success and to keep the Director calm. We are also very grateful to the host families in the village and neighbouring area, and to all who give so much time to ensure the smooth running of successive festivals.

Peter Barley